G’day there!

I suppose I probably should have written on this sooner. I certainly intended to back when I started this draft in July. But you know what they say about the road to Hell and good intentions and all that jazz. Anyway, better late than never.

As of July 5, 2015, quite possibly the historical exhibit of the year decade century has been open to the public at the Confederation Centre of the Arts’ Sobey Gallery in Charlottetown. Co-curated by the Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation, the Public Archives and Records Office of Prince Edward Island, and the Confederation Centre Art Gallery, in partnership with the Canadian Museum of History and Library and Archives Canada, and thanks in large part to the National Archives in London, the exhibit commemorates the 250th anniversary of the completion of Samuel Holland’s historic survey and map of the Island in 1765.

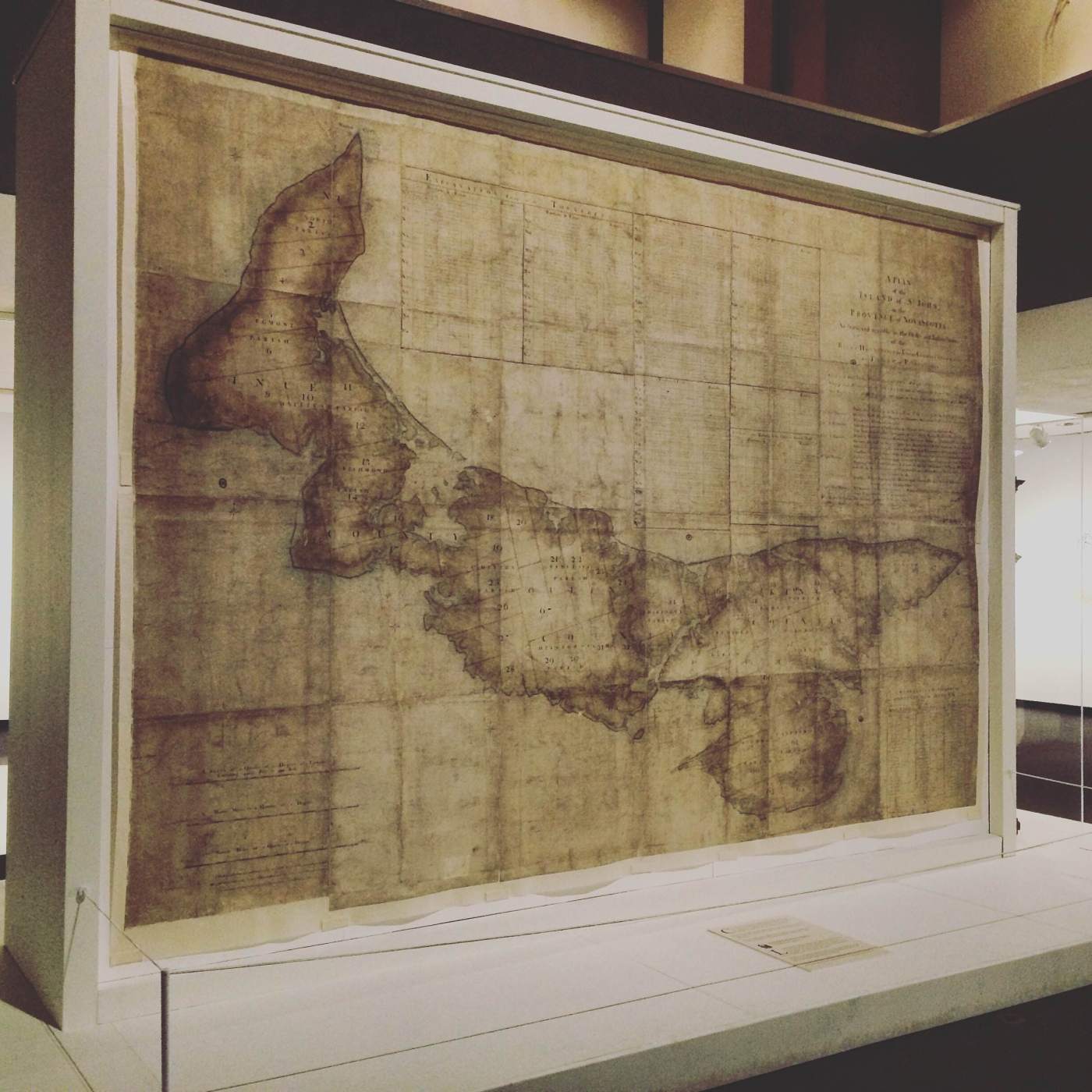

The exhibit features a delightful array of historic maps which pre- and post-date the Holland Map, as well as a selection of artefacts related to survey work of the period, and artefacts connected to Holland himself. However, the show-stopper, the piece de resistance, is the actual map itself, lovingly and painstakingly restored and beautifully mounted in all its 9′ x 12′ feet glory. What makes its presence so special is the fact that this is the first time that the Holland Map has returned to the Island, where it was compiled, since 1765.

I was fortunate enough to be able to attend the grand opening, along with many other people. During the ceremony , the Island’s Provincial Archivist, Jill MacMicken-Wilson made a very poignant remark: just as we (as Islanders) refer to the Island as “the Island” (suggesting there is no other in all the world), in the heritage community, Holland’s map is often referred to simply as “the Map”. Of course, there have been many maps of Prince Edward Island drawn up over the years, and a good many more that depict this province as part of a larger region; however, no other map (of the Island) has quite achieved the status, the renown that Holland’s labour has attained. In the history not only of Prince Edward Island, but also of cartography, his map represents a major watershed.

So, who exactly was this Samuel Holland chap, and why was his work so significant? Let’s take a gander.

His full name was Samuel Johannes Holland, and he was born in 1728 in Nijmegan, the Netherlands. About the age of 17, he embarked on what would become a military career when he joined up with the Dutch armed forces in 1745 amidst the War of the Austrian Succession. He was tapped for training in both artillery and fortifications, the latter considered to have provided him the foundational skills necessary for his future work in surveying and cartography.

Ambitious, and looking to better his prospects, in 1754 Holland opted to cast his lot with the British, and was given a lieutenant’s commission with the 60th Foot (Royal Americans). It was a switch that would eventually prove quite fortuitous. Between 1756 and 1763, he found himself embroiled in the Seven Years’ War (North American theatre), during which time he was promoted to captain, and found himself involved in a number of engineering projects that led to successful offensives against the French. The most notable of them occurred at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham in Quebec in September 1759, a key turning point in the conflict and one that witnessed the death of Generals James Wolfe (British) and Louis-Joseph de Montcalm (French). Holland himself was wounded in that battle, and was said to have been at Wolfe’s side when he fell.

From then on, the war began to go very much in Britain’s favour. By 1762, with the situation largely under control, Holland decided to pitch to his superiors the idea of surveying the Crown’s possessions in North America. Said superiors thought it a marvelous notion, and appointed him Surveyor-General of the Northern District. By 1763, the war had come to a close, and the next year, 1764, Holland set out on an 11-year journey which would earn him the reputation as the British army’s most qualified surveyor in North America – and one of its best in general. As for the survey, it would become the most monumental ever undertaken in the annals of cartography.

And it started right here, in little old P.E. of I.

Taking his orders from the Board of Trade and Plantations, Holland began his quest in Prince Edward Island, then St. John’s Island (formerly Ile Saint Jean). The Island had come firmly into British grasp in 1758, when the Acadian population here was expelled after opting to remain neutral during the Seven Year’s War. The Board of Trade then began to develop an eye to settling the Island. But first, it had to be surveyed.

Holland dropped anchor at the entrance to Charlottetown Harbour, and set up a base camp near Fort Amherst at a place now known as Holland Cove. He took along with him what, at the time, were some of the most advanced instruments science had to offer, and a team of officers, engineers, and rank soldiers. Once here, he even solicited the assistance of a few Acadian pilots (by this point, many who had escaped to refugee camps on the mainland had begun to work their way back – sneaky sneaky).

Work began in October 1764 and for the better part of a year, Holland and his men surveyed their way around the Island, often in harsh weather – and yes, even during the winter months! They took all the standard measurements and soundings, in addition to notes on just about everything else they could: forest resources, plant life, climate, possible land use, ideal sites for towns, and even astronomical observations. Most important, however, was the division of the Island into 67 lots, or townships, a fact that would prove crucial in defining the course of history here.

So – what to do with all of this information?

Holland likely had very little idea the enormity of the impact his survey and map would ultimately have. Not only was it, at the time, the most accurate map ever produced; as it turns out, it was precisely what the Board of Trade had hoped for, and quickly become a key component (you could say the key component) in Britain’s imperial plans for the Island. With more than enough data at hand to proceed with colonization efforts, the Island’s 67 lots as determined by Holland (minus one set aside for the Crown) were put into a lottery. During the course of a single afternoon in July 1767 each and every one of them was granted to well-placed/connected individuals. It was hoped that these proprietors would then actively attempt to encourage settlement of their lots, collect rent money, and funnel that money back up to the Crown’s coffers.

Well, that’s a pretty simplistic explanation. Suffice it to say that it didn’t quite go as planned, for a variety of reasons. But that’s a whole other post(s) unto itself.

After his work on the Island, Holland moved on. For the next two decades, he spearheaded additional surveys around the Atlantic region, the Thirteen Colonies, and Quebec before failing health chained him to office work. When he passed away in 1801, his widow and second wife, Marie-Josephte, relocated to his holdings on the Island at Tryon (he had drawn Lot 28 for his efforts). Some of his children had settled here shortly before; one of them, John Frederick, was born here sometime during the survey, and would go on to become a ‘mover ‘n a shaker’ in Island politics, as they say.

Anyway, that’s a bit a quickie on the life and times of Samuel Holland, and the significant role he played in shaping Island history. While I could go into greater detail, I feel I’ve already rambled enough as it is; however, if you’re hungry for more, there’s quite a bit of Holland literature that has been produced over the years, so I encourage you to seek it out. As for the exhibit, it runs until January 3, 2016 – if you haven’t been yet, don’t miss out!

Cheers,

PEI History Guy

December 5, 2015 at 12:19 am

I saw this exhibit and loved it, well curated and an eye opener on PEI History.

LikeLike

December 5, 2015 at 10:54 pm

That it is! I know a few of the people involved, and from what I hear, it took a lot of time and effort to put it all together – but well worth it, in the end!

LikeLike

January 5, 2016 at 1:05 pm

Reblogged this on Island Hearth.

LikeLike