G’day there!

Welcome to the very first installment of what I hope will be an informative, entertaining, and perhaps even an enlightening series of posts about the built heritage of Prince Edward Island. No matter where you go on the Island, there seem to be historic edifices around every turn in the road, with a variety of architectural styles represented, and each with a story to tell. The purpose of “Structures of Yesteryear” is to foster a greater appreciation of these buildings by sharing those stories.

I thought a good way to kick-start this series would be to profile an historic house that is near and dear to my heart, and has been for quite some time. I remember walking through it first when I was 8 years old, and have had the privilege of doing so many times since. Until just recently I was even fortunate enough to have my very own office in what was, at one time, part of the servants’ quarters on the second floor. Beaconsfield, this one’s for you.

In the 19th century, Prince Edward Island experienced a golden age because of an incredible shipbuilding boom, a boom that saw thousands of ships built and launched by shipyards which peppered the waterways from tip to tip. Initiated by Britain’s war(s) with Napoleon in the early 1800s and the need for lumber to build up its navy, shipbuilding simply took hold as an industry, and only waned about a hundred years later in the early 1900s. As with any industry throughout history, many people were lured by the prospect of money and jumped on the bandwagon. But as has always been the case, there were some who had a bit more luck then others, and grew to become the titans.

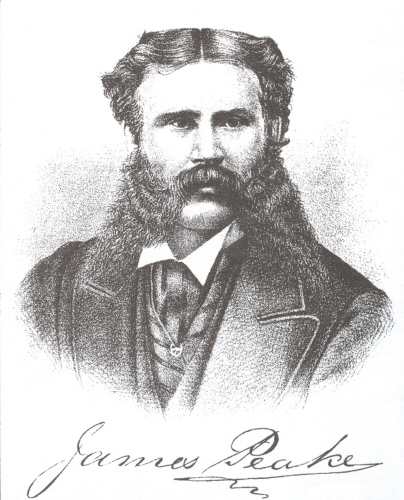

In 1877, one James Peake, Jr., found himself making a fortune in the family business of shipbuilding, as well as mercantile trade. He was making so much money, in fact, that he decided to build a house. But not just any old house. No, he wanted the house, one that would reflect his wealth. He purchased a plot of land in Charlottetown’s west end, a property with a magnificent view of the harbour (Fun Fact: When Peake purchased the site of Beaconsfield, it already contained a house which, although nice, did not quite meet his standards. So he put it up for sale and had it moved…across the street. We’ll take a look at this house in the next installment of Structures of Yesteryear!). And so arose on the corner of West and Kent Streets in Charlottetown what was considered for many years to be the finest and most opulent house in the city, if not the entire island. The Daily Examiner for June 2, 1877, ran the following piece:

“James Peake, Esq., is building a very fine residence on the beautiful site purchased by him from J.S. Carvell, Esq., last year [1876]. It will be completed sometime in August. W.C. Harris, Esq., is the architect. Mr. John Lewis, the builder.”

(Side note: W.C. Harris, or William Critchlow Harris, was an incredibly influential architect in Prince Edward Island, but I’ll write more about him in another post. Suffice it to say for now that, if you wanted the best house, then you required the services of the best architect.)

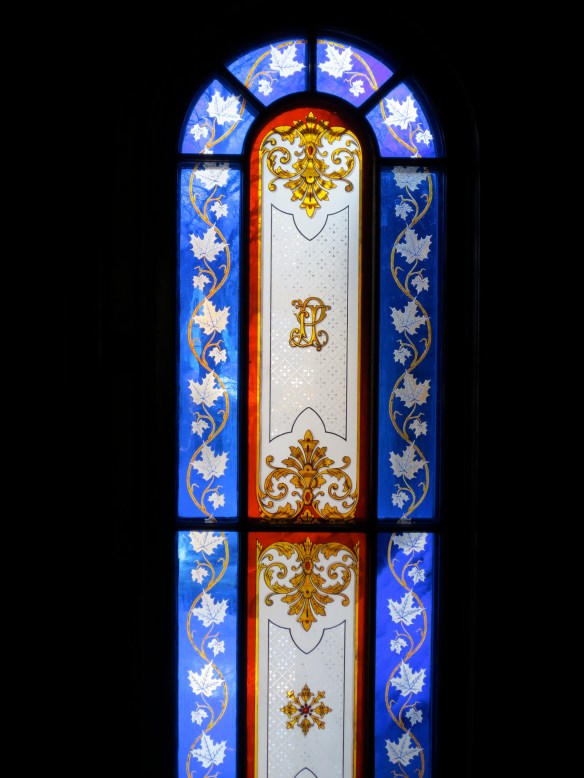

Named in honour of Benjamin Disraeli, the Earl of Beaconsfield, when the house was completed it was nothing short of stunning, exactly how Peake had envisioned it. A grand Victorian home blending Italianate and Second Empire styles, it came complete with 25 rooms, encaustic tile pavement in the front hall, bronze hardware on all the doors, eight marble fireplaces, cornices and ceiling rosettes, brass and Chinese porcelain chandeliers in the double drawing room and, to cap it all off, a magnificent second-floor stained glass window featuring a “J.P.” for James Peake. There could be no mistaking to whom this house belonged. Aside from the opulence, it was also incredibly modern for the times. Another resident of Beaconsfield, Henry Cundall, would later write in his diary that it was “completely furnished from cellar to observatory, with hot and cold water in the bedrooms [yes, the BEDROOMS], gas fittings in every room, and hall grates, and marble mantle pieces and other conveniences too numerous to mention.” And if you’re wondering about a price tag, try this on for size: Peake paid $50,000 dollars in 1877 to build his house, spending a sizeable $15,000 for the land, and a whopping $35,000 on the house itself. It sounds like a steal by today’s standards, but if you run it through an inflation calculator, it works out to the equivalent of $750,000 for the land and $1,750,000 for the house, bringing the total to a jaw-dropping $2,500,000 in today’s currency (although keep in mind that these numbers aren’t exact).

But money can’t buy happiness, as the adage goes, and it couldn’t have been more true for Peake and his family. He and his wife Edith (daughter of the Lieutenant Governor, no less), and their six children moved in in 1877 at the height of his prosperity; but in just six short years, the Peakes’ lost everything, including most of their children to sickness. You see, shortly after the house was built, PEI fell into a bit of an economic recession in 1880, and the shipbuilding industry began to tank, ruining Peake’s fortune. He and Edith were forced to give up their dream home when he declared bankruptcy in 1882, and in 1884 he was left with little choice but to leave Edith and his family behind while he moved out west to British Columbia, where he tried to eke out a living working in a snooker (pool) hall. Speaking with a magistrate upon his bankruptcy, he admitted the $50,000 he invested in Beaconsfield might have contributed to his financial ruin. His riches to rags story ends with his death, in poverty, in Vancouver in 1895.

With Peake in dire straits, the Cundall family, primary mortgagees of the property, were forced to take possession of Beaconsfield in 1883 in order to protect their investment. The house was put up for sale, the asking price a still-astronomical $35,000; however, they were willing to accept a measly $11,000 for it, the remainder of the mortgage, simply to break even. But times were tough and there weren’t any takers and so shortly after, Henry Cundall, land/business agent, surveyor, amateur photographer, and bachelor, along with Millicent and Penelope, his unmarried sisters, moved into a house he had no intention of moving into, despite seeming to wax poetic in his diary entry quoted above.

For a period of about thirty years, Beaconsfield was Cundall territory. In 1888, Millicent died, leaving Henry and Penelope in a house far too large for two people (naturally, they had domestics on staff, but even if you were to subtract the servants’ quarters, Beaconsfield would still be cavernous). During this time, Cundall continued with his survey work, spending his free time experimenting with photography and gardening. Every so often he would host exclusive lawn parties, hidden away behind a high board fence that concealed the property from view. When Penelope died in 1915, the house must have become even larger for Henry, whose health subsequently declined. In 1916, he passed away a bachelor. With no children of his own to whom he could will Beaconsfield, he stipulated in his will that it was to be a “refuge and temporary home for friendless young women.” Despite the fact that the house sat vacant for a bit, his wish became a reality when the doors reopened as a Y.W.C.A. (Young Womens Christian Association), called the “Cundall Home”. Girls attending the Prince of Wales College (present-day Holland Collage) on the other side of town were given lodging there, as were tourists in the summer months.

In 1935, Beaconsfield became a residence for nursing students training at the old Prince Edward Hospital on Brighton Road, and remained so until 1971. In that year, the Centennial Committee established to commemorate the Island’s entry into Confederation in 1873 advocated for its purchase and restoration, to be used jointly as the headquarters for the newly formed Prince Edward Island Museum and Heritage Foundation, and an historic house showcasing the house’s Victorian splendour. Upon completion of the restoration, Beaconsfield Historic House was officially opened by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in July of 1973.

It’s been almost 137 years since Beaconsfield was built. But it hasn’t lost any of its magnificence, and its history only continues to grow.

Cheers,

PEI History Guy

P.S. – Fun Fact: Did you know that in 1879 (before the Peake family went bankrupt!) Beaconsfield played host to a dinner party that the Daily Examiner claimed to be “the best ever given in the Island”? More to come in a future post!

March 23, 2015 at 1:54 pm

Hi PEI History Guy,

Thank you for this. I used to work at Beaconsfield, miss it a lot. It’s nice to see it and read about it in this way

LikeLike

March 23, 2015 at 2:12 pm

Hi Tracy,

Thanks for reading! I have fond memories of the house myself. Although I never worked there for the Museum and Heritage Foundation, I did occupy office space on the second floor when I worked for the Provincial Archaeology Office. It was a privilege to walk through those halls every day.

LikeLike